Somewhat confusingly Holy Trinity is in Hertford Heath and Little Amwell doesn't appear to exist as a village but the church board begs to differ.

I'd been here before, took a passing glance and drove on, which I think was a mistake. Built in 1863 by Ewan Christian to serve the congregation of Little Amwell who met in the school and whose nearest church was in Hertford itself - a walk that, whilst not long, was probably dis-inspirational - the building should be all that I abhor in Victoriana...but its not.

I like the apse and hate the 'spire', the transepts and porch are awful but overall it's appealing - I think it's the nave roof that swings it, because the rest of the fittings are dull.

Mee didn't bother and I'm worried about liking a Victorian church - again.

Flickr.

Statcounter

Friday 23 September 2011

Wednesday 14 September 2011

Willian

Willian lies just outside my travel border but, having seen photographs of All Saints on Flickr, I added it to the trip as it fell close enough to Buckland and Ardeley (which I still didn't get into as the keyholders were out) to make a detour.

The exterior has some truly amazing grotesques on the tower including a man with a bible and Death which were exciting but not exciting enough to make up for the fact that the church is kept padlocked and no keyholder is listed.

ALL SAINTS. In the chancel is a C12 blocked doorway. The rest appears C14 and chiefly C15. The chancel E window is specially attractive with two orders of shafts inside. Early in the C19 the E end received some blank Dec arcading and a reredos to match. - SCREEN. Little of the C15 left. - CHANCEL SEATS. With poppyheads; also one with an elephant and castle and one with St John’s head on the charger. - PLATE. Chalice and Paten, 1718. - MONUMENTS. Brass to Richard Golden d. 1446, frontal, in priest’s vestments. - Epitaph with the two usual kneelers to E. Lacon d. 1625 and an even humbler one with kneelers to John Chapman d. 1624. - Sir Thomas Wilson d. 1656 and wife, with two frontal busts in oval niches above long inscription.

The exterior has some truly amazing grotesques on the tower including a man with a bible and Death which were exciting but not exciting enough to make up for the fact that the church is kept padlocked and no keyholder is listed.

ALL SAINTS. In the chancel is a C12 blocked doorway. The rest appears C14 and chiefly C15. The chancel E window is specially attractive with two orders of shafts inside. Early in the C19 the E end received some blank Dec arcading and a reredos to match. - SCREEN. Little of the C15 left. - CHANCEL SEATS. With poppyheads; also one with an elephant and castle and one with St John’s head on the charger. - PLATE. Chalice and Paten, 1718. - MONUMENTS. Brass to Richard Golden d. 1446, frontal, in priest’s vestments. - Epitaph with the two usual kneelers to E. Lacon d. 1625 and an even humbler one with kneelers to John Chapman d. 1624. - Sir Thomas Wilson d. 1656 and wife, with two frontal busts in oval niches above long inscription.

Still, the vicar, or whoever, does have an interesting sense of humour:

Willian. Many who come on this homely place with its green and its ponds, its tall trees, its medieval church, and its thatched vicarage 400 years old, must think it an endearing English scene, fit to be preserved for ever; and so it is to be, for it stands within the green belt bought by Letchworth’s Garden City.

Limes and chestnuts strive to out-top the gargoyles of death and the other dread powers peering out from the 15th century tower. Graver medieval heads, 14 in all, support the chancel roof, and tiny heads below them add to the delicate arcading. The 15th-century woodcarvers added their quaint fancies to the posts of the choir stalls, where we see a sphinx-like monster with barbed tail above the Baptist’s head on a charger; and strangest of all is a perfect little elephant bearing a howdah with openings carved like medieval church windows. Part of a Tudor screen is left in the 15th century chancel arch, which matches the arch of the tower. The walls of the nave and the chancel are the work of Norman masons.

Two vicars of long ago are here in brass and stone, Richard Goldon having a portrait brass of 1446 on the chancel wall, and John Chapman, who died in 1624, appearing as a small kneeling figure in stone with his wife. By the altar kneel more stone figures, Edward Lacon with his wife and three children. The father, who is in armour, died in the year Charles I came to the throne. Thirty years later, when Cromwell ruled in Charles’s place, another monument was set here with the busts of a man and his wife looking out from dark recesses. He is Thomas Wilson, who died while he was serving as Prefect here under Cromwell’s military system of local government, when the whole of England was divided into ten areas and each area was ruled by a major-general.

Tuesday 13 September 2011

St Michael, Bishop's Stortford

Taking advantage of having two students at home, an orthodontist appointment for middle son and the youngest back at school I decided to do a revisit trip and Bishop's Stortford. The planned route was Bishop's Stortford (three churches), and then revisits to Sacombe, Braughing, Ardeley, Willian (which was not a revisit but sat well with the route), Buckland and Wydiall.

I knew when I set off that this would be a bit hit and miss and so it proved.

St Michael in Bishop's Stortford was the first hiccup with a service in progress which was to be followed by a toddlers get together. I've photographed this church before but lost the pictures in a blue screen event shortly afterwards. As the middle son still goes to school in Stortford this is not a disaster.

The exterior is almost impossible to shoot due to a tight churchyard and intervening trees; I was surprised to learn from Mee that the main body of the church is old - I've always thought that it was a 19th century build but that's only the spire.

UPDATE: I photoed the interior in November 2010 with a Kodak EasyShare camera - essentially a digital disposable camera - having assumed that there would be little of interest within...how wrong I was. I had some pretty poor images of the amazing misericords and knew a revisit with the grown up camera was required - it took me until today (30.01.12) to achieve a successful shoot despite regular visits to Stortford.

ST MICHAEL. A big, low, embattled Perp town church with a W tower and tall spire, prominent for a long distance around, not owing to the early C15 which built it (set-back buttresses, low stair turret) but to the year 1812 when a tall, slim upper stage of light brick was added, with buttresses at the angles and pinnacles above and a lead spire. The contrast between the business-like sturdiness below and the fragility above is that between Gothic and Gothick. The whole church is otherwise of the C15 (except for the C19 N chancel chapel and tall S Vestry) with typical Late Perp windows, with depressed segmental or depressed pointed arches (the latter with almost straight sides), with a N porch two bays deep and a S porch. The chancel clerestory and chancel E window belong to the C19. The original E window of three lights is now in the S wall. The interior is big and airy. Tall tower arch on thin responds, six-bay arcade with thin piers (four main shafts and four hollows in the diagonals) and two-centred arches, two-light clerestory windows, lower chancel. The roofs of nave, chancel, and aisles are original. In the nave the arched braces are traceried, and they rest on stone corbels with the figures of the Apostles. In the aisles instead of these there are grotesques and also such genre figures as a gardener with pruning knife, a cook with ladle, a woodman with bill-hook, etc. - FONT. C12, square, of Purbeck marble, with shallow blank arches;on five supports.- ALTAR AND SURROUND. 1885, by Sir A. Blomfield. - PULPIT. Locally made for £5 in 1658, an extremely late date for so purely Elizabethan a piece. The angles have termini pilasters decorated with raised ovals and diamonds. This and the decoration of the main panels with arches in feigned perspective probably comes straight from some pattern book. - SCREEN. C15; big, with two tall four-light sections on each side of the entrance. - CHANCEL STALLS. C15, with poppy-heads at the ends of the front stalls and MISERICORDS for their back seats. They represent inter alia heads of human figures and animals, very well carved, an angel, a swan, an owl, a dragon. - DOORS. Original, both in N and S porches. - STAINED GLASS. Chancel S window, by Powell, 1853 (TK), still in the painting tradition of the C18; not yet medievalizing. - W window, by Kempe, 1877, a very characteristic example of his early manner. - PLATE. Paten, 1563; Chalice, 1597; Chalice, 1683; two Flagons, 1721; Almsdish, 1741. - No monuments of any importance.

Bishop’s Stortford. The greatest thing it has done for the world was to give birth to Cecil Rhodes, and we may believe that the time will come when the house in which he was born will be a place of pilgrimage. Yet this small town had its place in history centuries before young Rhodes sat in the pews at St Michael’s listening to his father preach. In the public gardens is a mound on which it is believed a castle stood, Waytemore Castle, the fortress of Bishop Maurice of London, into whose hands the Conqueror entrusted this key position by the ford over the River Stort. The outer works and moats can be traced among the walks and flowerbeds.

I knew when I set off that this would be a bit hit and miss and so it proved.

St Michael in Bishop's Stortford was the first hiccup with a service in progress which was to be followed by a toddlers get together. I've photographed this church before but lost the pictures in a blue screen event shortly afterwards. As the middle son still goes to school in Stortford this is not a disaster.

The exterior is almost impossible to shoot due to a tight churchyard and intervening trees; I was surprised to learn from Mee that the main body of the church is old - I've always thought that it was a 19th century build but that's only the spire.

UPDATE: I photoed the interior in November 2010 with a Kodak EasyShare camera - essentially a digital disposable camera - having assumed that there would be little of interest within...how wrong I was. I had some pretty poor images of the amazing misericords and knew a revisit with the grown up camera was required - it took me until today (30.01.12) to achieve a successful shoot despite regular visits to Stortford.

ST MICHAEL. A big, low, embattled Perp town church with a W tower and tall spire, prominent for a long distance around, not owing to the early C15 which built it (set-back buttresses, low stair turret) but to the year 1812 when a tall, slim upper stage of light brick was added, with buttresses at the angles and pinnacles above and a lead spire. The contrast between the business-like sturdiness below and the fragility above is that between Gothic and Gothick. The whole church is otherwise of the C15 (except for the C19 N chancel chapel and tall S Vestry) with typical Late Perp windows, with depressed segmental or depressed pointed arches (the latter with almost straight sides), with a N porch two bays deep and a S porch. The chancel clerestory and chancel E window belong to the C19. The original E window of three lights is now in the S wall. The interior is big and airy. Tall tower arch on thin responds, six-bay arcade with thin piers (four main shafts and four hollows in the diagonals) and two-centred arches, two-light clerestory windows, lower chancel. The roofs of nave, chancel, and aisles are original. In the nave the arched braces are traceried, and they rest on stone corbels with the figures of the Apostles. In the aisles instead of these there are grotesques and also such genre figures as a gardener with pruning knife, a cook with ladle, a woodman with bill-hook, etc. - FONT. C12, square, of Purbeck marble, with shallow blank arches;on five supports.- ALTAR AND SURROUND. 1885, by Sir A. Blomfield. - PULPIT. Locally made for £5 in 1658, an extremely late date for so purely Elizabethan a piece. The angles have termini pilasters decorated with raised ovals and diamonds. This and the decoration of the main panels with arches in feigned perspective probably comes straight from some pattern book. - SCREEN. C15; big, with two tall four-light sections on each side of the entrance. - CHANCEL STALLS. C15, with poppy-heads at the ends of the front stalls and MISERICORDS for their back seats. They represent inter alia heads of human figures and animals, very well carved, an angel, a swan, an owl, a dragon. - DOORS. Original, both in N and S porches. - STAINED GLASS. Chancel S window, by Powell, 1853 (TK), still in the painting tradition of the C18; not yet medievalizing. - W window, by Kempe, 1877, a very characteristic example of his early manner. - PLATE. Paten, 1563; Chalice, 1597; Chalice, 1683; two Flagons, 1721; Almsdish, 1741. - No monuments of any importance.

Bishop’s Stortford. The greatest thing it has done for the world was to give birth to Cecil Rhodes, and we may believe that the time will come when the house in which he was born will be a place of pilgrimage. Yet this small town had its place in history centuries before young Rhodes sat in the pews at St Michael’s listening to his father preach. In the public gardens is a mound on which it is believed a castle stood, Waytemore Castle, the fortress of Bishop Maurice of London, into whose hands the Conqueror entrusted this key position by the ford over the River Stort. The outer works and moats can be traced among the walks and flowerbeds.

The hilly streets of Bishop’s Stortford set off to advantage the fine old buildings among the new, many of them inns from the 16th to I7th centuries with overhanging storeys; the Boar’s Head and the timbered Black Lion still carrying on, the White Horse, with its plastered heraldic front of Italian work, an inn no longer.

Two fine churches, an old one and a new one, look to each other across the roofs of the town, both set on hills. The new church is All Saints, the old one is St Michael’s. The new one, looking out over the town from Hockerill, was designed by Mr Dykes Bower, and is one of the best modern churches we have seen. It has a magnificent rose window in the east with Christ in the centre surrounded by dazzling colours, rings of little suns, flames, and symbols. The west window has three great plain lancets in the tower. There are four high arches on each side of the nave, supported by round columns, the stone roof is spaced out in 125 compartments, and there is a charming oriel in the sanctuary.

But the eye turns first and last in this town to the splendid 500 year-old church shooting up its pinnacled tower and spire from among the houses on the top of the other hill, summoning its worshippers with a peal often bells. The spire was added in 1812. They enter today by the very door people pushed open five centuries ago, and in one spandrel of the doorway is the same strange carving of the All-Seeing Eye, the Angel of the Resurrection sounding his trumpet in the opposite spandrel. The door opens on the six great bays of the spacious nave and aisles, where corbels of angels and apostles and medieval folk turn on us their stony gaze; we noticed a gardener, a cook, and a woodman among them. Save for a few changes and additions the church is wholly medieval, and has a Norman font which has been buried, having probably belonged to the church before this. There are 18 rich choir stalls, making a grand show with their traceried backs and panelled fronts, and misericords crowded with 15th-century faces and fancies, men and animals, one of them a rare early carving of a whale. The fine chancel screen is mainly 15th century, but the vaulting is new. The pulpit and a remarkable chest are Jacobean, the chest having an inside lock of 14 bolts which are as long as the lid. Both the north chapel and south vestry are Victorian.

There is a tablet in this fine church to a man who made the River Stort navigable up to Bishop’s Stortford. He befriended Captain Cook, who showed his gratitude by making him known to navigators all over the world, naming after him Port Jackson in New South Wales and Point Jackson in New Zealand. The man whose name thus lives on the map was born George Jackson at Richmond in Yorkshire, but he died Sir George Duckett; here in the church is his memorial. We find no memorial to a butcher’s son born here in 1813, who did much to help photography by proving the use of collodion in developing films. He was Frederick Scott Archer, and his children were pensioned by the Crown because his invention brought him no profit but yielded vast profits for others.

Much happier in his fortune was the famous physician who lies in the Quaker burial ground; he was Thomas Dimsdale, an Essex man who adopted Hertfordshire as his county, practised as a doctor in the county town, and sat in Parliament for it. He is remembered for his pioneering with inoculation for smallpox, and especially because Catherine of Russia invited him to her capital to inoculate herself and her son. It was in 1768, when the adventure was fraught with some peril, and the empress arranged for relays of horses from the capital to the border to aid the doctor’s escape in case of disaster. Happily all was well, and Dimsdale received £2000 for expenses, a fee of £10,000, and an allowance of £500 a year. He was laid in the burial ground of the Quakers here when he was 89 years old.

One of the windows of St Michael’s is in memory of the old vicar Francis Rhodes, who was laid to rest here eight years after his delicate son had left for South Africa. He lived to hear the good news that his son had found health and strength and was working in the diamond digging, and he saw him home again entering on a graduate’s life at Oxford; but he died in 1878 before Cecil entered the Cape Parliament, and before he had formed his great plan of a British South Africa. In the birthplace we see his portrait looking down from the wall on the bed in which Cecil Rhodes was born.

Bishop’s Stortford has been long in paying homage to its great son, but it has made amends, has bought the house he was born in and the house next door, and is developing both as a Cecil Rhodes Museum. The house is refurnished with pieces that either belonged to the family or belonged to the time, and it is an attractive place for any pilgrim interested in Rhodes of Rhodesia. In addition to the bed he was born in, one of eleven children, there is here the Bible his mother gave him, a fine old clock which was ticking in those days, a picturesque native drum used for communicating signals, a water colour he painted of a windjammer, and the uniforms he wore on ceremonial occasions - and never again.

Cecil Rhodes’s birthplace has all the glamour and fascination that invests the homes of famous men, and it is gratifying to find how much this great empire-builder’s memory is honoured in his native town.

Sunday 11 September 2011

Hinxworth

The lovely St Nicholas shouldn't, on paper, be lovely at all but somehow the C18th brick chancel works well with the earlier nave and tower. Whilst it contains many points of interest its crowning glory is the chancel brass to John Lambard which includes an image of his daughter Jane (aka Elizabeth) Shore who became Edward IV's mistress.

ST NICHOLAS. Nave without aisles, low W tower with angle buttresses, chancel of C18 brick. The rest is mixed stone and flint. S porch with three-light windows as at Ashwell. Inside the church two niches for statues, one on the E side of a N window, the other in the SE corner of the nave. - BRASSES. Man and woman, mid C15 (chancel N wall). - Man and woman, nearly 4 ft long with, below, individually cut and mounted figures of six children. Late C15, unusually good, believed to be John Lambard d. 1487, Alderman of London.

Hinxworth. Old Robert Clutterbuck, who devoted years to making a history of his beloved Hertfordshire, lived at Hinxworth Place, a perfect home for an antiquarian, for this stone house was built in the I5th and 16th centuries, with mullioned windows of old glass, pointed doorways, and panelled walls set in a lovely garden - all within a mile of the thatched cottages and the quaint clock tower of the village among the elms. Happily its beauty is safe, for it belongs to the county council, and every passer-by may feel that he shares its freehold. Here Robert Clutterbuck toiled for 18 years on his three volumes of Hertfordshire, published over a period of 12 years, beginning at the time of Waterloo. It has been said that the plates in his work have never been surpassed in such a publication.

ST NICHOLAS. Nave without aisles, low W tower with angle buttresses, chancel of C18 brick. The rest is mixed stone and flint. S porch with three-light windows as at Ashwell. Inside the church two niches for statues, one on the E side of a N window, the other in the SE corner of the nave. - BRASSES. Man and woman, mid C15 (chancel N wall). - Man and woman, nearly 4 ft long with, below, individually cut and mounted figures of six children. Late C15, unusually good, believed to be John Lambard d. 1487, Alderman of London.

Hinxworth. Old Robert Clutterbuck, who devoted years to making a history of his beloved Hertfordshire, lived at Hinxworth Place, a perfect home for an antiquarian, for this stone house was built in the I5th and 16th centuries, with mullioned windows of old glass, pointed doorways, and panelled walls set in a lovely garden - all within a mile of the thatched cottages and the quaint clock tower of the village among the elms. Happily its beauty is safe, for it belongs to the county council, and every passer-by may feel that he shares its freehold. Here Robert Clutterbuck toiled for 18 years on his three volumes of Hertfordshire, published over a period of 12 years, beginning at the time of Waterloo. It has been said that the plates in his work have never been surpassed in such a publication.

Reached by a shady field path, where two Lombardy poplars frame a distant view of the Essex hills and limes form a double guard to the door, is a church of about the time of Agincourt, with a Tudor clerestory and 18th-century brick chancel. In the 15th-century porch we found a stone coffin lid 600 years old. Four ancient oak angels stand out darkly against the newer roof, and canopied stone niches make beautiful two window-sills. Excelling in beauty is a brass on the chancel floor, a superb portrait of John Lambard, Master of the Mercers Company, buried here in 1497. His wife, their daughter, and three sons, are with him in elegant dress. An earlier unknown couple who would know this church when it was new 500 years ago have their brass portraits on the wall.

At Hinxworth was found a Venus brought here by some art-loving Roman in the days of the Caesars, whose coins have also been found in plenty; and a gravel pit older than the Romans has yielded traces of four distinct British tribes.

Ashwell

Ashwell was evidently a wealthy town back in the day since St Mary is monumental, the tower is visible for miles around. Surprisingly for all its massiveness the main points of interest here are graffiti.

In the tower there's some Latin script and a drawing of a church both of which are interesting.

The Latin graffiti records the Black Plague in 1348 and the great wind of 1361 and reads:

There was a plague 1000 three times 100, five times 10 a pitiable fierce violent (plague departed) a wretched populace survives to witness and in the end a mighty wind Maurus, thunders in this year of the world, 1361.

The storm on St Maur’s Day blew down the spire of Norwich Cathedral. William Langland, the poet, who was about 30 years old at the time, wrote that the broad oak trees were ’turned upwards by their tailles’.

The church is supposed to show the north elevation of Old St Paul's cathedral. It shows a central tower and a tall spire with flying buttresses. The Rose window at the east end is turned 90 degrees so that it can be shown in the same drawing. It is thought to date between 1360, when Ashwell tower was built and 1561 when the spire of St Paul fell down.

On the westernmost column of the north aisle is another drawing of a church which is better preserved.

ST MARY. The glory of the church is its W tower, in four stages with tall angle buttresses. It is 176 ft high, crowned by an octagonal lantern with a leaded spike, the same pattern as at Baldock. The tower is clunch-built and more ambitious than any other of a Herts parish church, and it has never been explained why just Ashwell should have gone to such an enormous expense. It was begun in the first half of the C14.* The church itself is of the same date, the chancel was apparently completed in 1368, and the whole building in 1381. The body of the church is of clunch and flint, relatively low and not embattled except for the chancel. Most of the windows are usual C15 Perp, but the clerestory windows and the tower W window prove that the Dec style was still alive when the building went up. The S porch is two storeyed, higher than the aisle, with a fine outer doorway and two-light windows (the vault is C19). The N porch of one storey has three-light windows. Both porches are of the second half of the C15. The interior bears out the building history surmised for the exterior. The arcades of the nave look indeed a little earlier than 1350. They change their details from E to W (piers with big attached shafts and thin ones without capitals in the diagonals, then piers with the big shafts slightly thinner, then with the big shafts of semi-octagonal section). The aisle roofs are good, solid C14 work. The chancel arch corresponds to the earlier parts of the nave, the tower arch to the later. To link up nave and tower a blank piece of wall was left standing and decorated with a blind two-light Perp arch as high as the whole nave. The clerestory windows stand above the spandrels, not the apexes of the arcade. The chancel is aisleless with large windows, and as these have no stained glass it appears very light. The whole church is indeed spacious and broad, rather than tall. The walls are whitewashed, the stone parts light. The effect is decidedly puritanical, especially as the church has surprisingly little of furnishings. - PULPIT. 1627. The usual blank arches in the panels are made up of diamond-cut pieces. - LADY CHAPEL SCREEN. Very elementary C15 tracery. - STAINED GLASS. Small C15 fragments in clerestory windows. - PLATE. Paten, 1632; Chalice, 1688. - No monuments of importance. - LYCHGATE. Attributed to the C15.

* This is proved by the extremely interesting graffiti inside the N wall of the tower. They say in Latin: ‘MCterX Penta miseranda ferox violenta . . .(? pestis) superest plebs pessima testis’ and ‘In fine ije (secundae) ventus validus . . . . . .. . Maurus in orbe tonat MCCCXI, 1350, wretched, wild, distracted. The dregs of the mob alone survive to tell the tale. At the end of the second (outbreak) was a mighty wind. St Maurus thunders in all the world.’ The date of this exceptional gale was 1361. Higher up on the tower wall (N) there is a further inscription, in much smaller script: primula pestis in MterCCC fuit 1.minus uno. Also on the N wall a remarkably detailed and accurate scratching of the S side of Old St Paul’s cathedral.

In the tower there's some Latin script and a drawing of a church both of which are interesting.

The Latin graffiti records the Black Plague in 1348 and the great wind of 1361 and reads:

There was a plague 1000 three times 100, five times 10 a pitiable fierce violent (plague departed) a wretched populace survives to witness and in the end a mighty wind Maurus, thunders in this year of the world, 1361.

The storm on St Maur’s Day blew down the spire of Norwich Cathedral. William Langland, the poet, who was about 30 years old at the time, wrote that the broad oak trees were ’turned upwards by their tailles’.

The church is supposed to show the north elevation of Old St Paul's cathedral. It shows a central tower and a tall spire with flying buttresses. The Rose window at the east end is turned 90 degrees so that it can be shown in the same drawing. It is thought to date between 1360, when Ashwell tower was built and 1561 when the spire of St Paul fell down.

On the westernmost column of the north aisle is another drawing of a church which is better preserved.

ST MARY. The glory of the church is its W tower, in four stages with tall angle buttresses. It is 176 ft high, crowned by an octagonal lantern with a leaded spike, the same pattern as at Baldock. The tower is clunch-built and more ambitious than any other of a Herts parish church, and it has never been explained why just Ashwell should have gone to such an enormous expense. It was begun in the first half of the C14.* The church itself is of the same date, the chancel was apparently completed in 1368, and the whole building in 1381. The body of the church is of clunch and flint, relatively low and not embattled except for the chancel. Most of the windows are usual C15 Perp, but the clerestory windows and the tower W window prove that the Dec style was still alive when the building went up. The S porch is two storeyed, higher than the aisle, with a fine outer doorway and two-light windows (the vault is C19). The N porch of one storey has three-light windows. Both porches are of the second half of the C15. The interior bears out the building history surmised for the exterior. The arcades of the nave look indeed a little earlier than 1350. They change their details from E to W (piers with big attached shafts and thin ones without capitals in the diagonals, then piers with the big shafts slightly thinner, then with the big shafts of semi-octagonal section). The aisle roofs are good, solid C14 work. The chancel arch corresponds to the earlier parts of the nave, the tower arch to the later. To link up nave and tower a blank piece of wall was left standing and decorated with a blind two-light Perp arch as high as the whole nave. The clerestory windows stand above the spandrels, not the apexes of the arcade. The chancel is aisleless with large windows, and as these have no stained glass it appears very light. The whole church is indeed spacious and broad, rather than tall. The walls are whitewashed, the stone parts light. The effect is decidedly puritanical, especially as the church has surprisingly little of furnishings. - PULPIT. 1627. The usual blank arches in the panels are made up of diamond-cut pieces. - LADY CHAPEL SCREEN. Very elementary C15 tracery. - STAINED GLASS. Small C15 fragments in clerestory windows. - PLATE. Paten, 1632; Chalice, 1688. - No monuments of importance. - LYCHGATE. Attributed to the C15.

* This is proved by the extremely interesting graffiti inside the N wall of the tower. They say in Latin: ‘MCterX Penta miseranda ferox violenta . . .(? pestis) superest plebs pessima testis’ and ‘In fine ije (secundae) ventus validus . . . . . .. . Maurus in orbe tonat MCCCXI, 1350, wretched, wild, distracted. The dregs of the mob alone survive to tell the tale. At the end of the second (outbreak) was a mighty wind. St Maurus thunders in all the world.’ The date of this exceptional gale was 1361. Higher up on the tower wall (N) there is a further inscription, in much smaller script: primula pestis in MterCCC fuit 1.minus uno. Also on the N wall a remarkably detailed and accurate scratching of the S side of Old St Paul’s cathedral.

Ashwell. Set among trees in a countryside of open fields on the Cambridgeshire border, it is one of the pleasant surprises of this part of the county. As we look down from the low hills about it, it is a charming picture with its roofs clustering round a weather-worn church. Some of the many old houses have overhanging storeys and roofs of thatch and tile; some are timbered, and one has remains of ornamental plasterwork. The village also has an inn rejoicing in the quaint name of Bushel and Strike. Deep down below the road the River Rhee, a tributary of the Cam, comes to life. The ash trees growing about the spot, spreading their branches on a level with the road, are said to have given the village its name.

One of the old buildings near the church is the 17th-century Merchant Taylors School, now part of a larger school. Another is a timbered medieval cottage with gabled roof, quaint windows, old fireplaces, and huge oak beams - charmingly restored as a little museum for housing the collection of local relics of bygone days which was begun by two enthusiastic schoolboys, who collected antiquities and conducted excavations as if they had been learned professors on a happy hunting ground. A hundred years ago the cottage was a tailor’s shop, and before that it was the Tythe House.

In the museum are some bits of wool and a few wheat grains that were left in a crevice of the old building from the harvests of years ago. Old Ashwell is represented here in all its ages. There is a rare specimen of a polished Neolithic tool, coins from Roman days down through history, old straw plaiting tools, and a long metal harvest horn which woke the men of Ashwell from their beds at four in the morning. The museum is the pride of the village, and we heard of labourers hurrying off to it with fresh finds turned up by their ploughs. South-west of Ashwell are the entrenchments known as Arbury Banks, a vast circle of ploughed field, half-surrounded by broad deep banks, now cared for by the Ministry of Works. Once it was a Roman settlement, and earlier still the great banks protected the pit dwellings of an ancient people.

Reached by a worn lych gate, which may be 15th century, the great church reminds us of the time when Ashwell was a prosperous market town with four fairs a year. Very striking is the 14th-century tower, with rough and heavy stepped buttresses climbing nearly to the top, and crowned with a slight leaded spire set on an octagonal drum. Records of days gone by are cut on the wall of the tower and on the pillars of the nave, a Latin inscription telling of the days when terror fell upon the people of England and the Black Death struck dead one man in three: "Miserable, wild, and distracted, the dregs of the people alone survive to witness; and in the end a tempest." Ashwell tower stood out against the tempest, but the tower of neighbouring Bassingbourn crashed to the ground. Below the inscription on Ashwell’s tower is a fine though much worn drawing of 1350 showing a cathedral, very like Old St Paul’s, which was completed that year and must have been in every architect’s mind. It is scratched on the wall of the tower and the drawing of a simpler church is on a pillar of the north arcade. A sheet of lead in the tower, once on the roof, has an inscription saying that Thomas Everard laid it here to lie 100 years; he would be glad to know that it lay 200 years, and has only had to be replaced in our own time.

The church is as long as the tower and spire are high, and is chiefly 14th century, with porches added and some of the windows altered a century later. The clerestory is partly 16th century. The original window of the north aisle has beautiful butterfly tracery, with quaint heads of a man and a woman at each side. The high tower of diminishing stages has fine windows, and striking double buttresses stepped and gabled. The south porch, higher than the nave, has a niche in the gable, and modern vaulting. The old door within it opens to a stately interior full of light from clear glass. The nave arcades have clustered pillars on high bases, and among the figures of men, women, and animals between their arches are two men grimacing, and a man thoughtfully stroking his beard. The walling at the west end of each arcade is carved with tracery like windows, reaching from floor to roof.

Bright as a summer noonday, the beautiful chancel has fine sedilia and a piscina with only half a bowl, a stone panel carved with the Last Supper under the great east window, a niche in a window splay with an animal carved under the bracket, and the base panels of the 15th-century screen, with poppyheads of a griffin and a quaint fish at each side of the entrance. Rich medieval screen work encloses the north chapel. The pedestal pulpit is 1627, and a 17th century chest has carving and iron bands. A floorstone to John Sell of 1618 has these words: To God a Saint, to Poore a Friend.

Flickr

Flickr

Saturday 10 September 2011

Caldecote

St Mary Magdalene has been taken under the wing of The Friends of Friendless Churches. The present church dates from the 14th and 15th centuries. It is likely that there was an earlier church on the site as the list of rectors begins in 1215. The village was abandoned during the 15th and 16th centuries. Repairs were carried out to the church in the 18th century and the church was declared redundant in 1975. It was taken into the care of the charity, the Friends of Friendless Churches, in 1982.

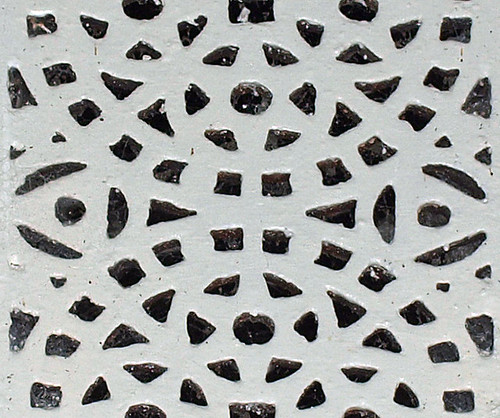

St Mary Magdalene is constructed in flint and clunch rubble, with some brick. The clunch came from a nearby quarry at Ashwell. The brick was inserted to replace worn-away clunch. It is a small church with a nave and chancel without any division between them. It measures 51 feet (15.5m) long by 14 feet 6 inches (4.4m) wide. At the west end is a tower in two stages with corner buttresses in the lower part of the bottom stage. There are two-light windows dating from the 14th century in both stages and a plain parapet at the summit. On the east face of the tower is a lead plaque inscribed "Katherine Morris 1736", an unusual reference to a female plumber responsible for the lead covering on the roof. On the south of the church is a porch dating from the 15th century. The nave, chancel and porch have battlemented parapets. The windows in the nave and chancel are Perpendicular in style. Inside the porch is a crocketed and canopied stoup, which Nikolaus Pevsner states is unique. The font dates from the 15th century; it is octagonal with carved tracery, shields, and foliage, in "unusually rich" Perpendicular style. The benches also date from the 15th century, as does the circular east window. The memorials include a kneeling figure of Rector William Makesey who died in 1424. There is also a plaque to the memory of Thomas Inskip, 1st Viscount Caldecote.I loved this church and in many ways, although they couldn't be more different, it reminded me of Tilty - think it might have been the quality of light and the seamless nave and chancel.

There's a tragically ruined, I think Flemish but maybe old English, window which appears to be beyond redemption, it looks like damp problems, but some of the panes are still discernible. It depicts the story of Christ and I imagine the lower pains depicted the passion sequence and resurrection but it's impossible to say for sure.

From the south it looks like a Hobbit town church.

ST MARY MAGDALENE. The stone built church stands like a miniature model on the grass, N of the barns of a big farm. The W tower starts broad and then, by means of hips, goes narrower. The tower windows seem to be of the late C14. The nave and chancel windows are Perp and of modest dimensions. There is inside no structural division between the two parts. The only more ornamental part of the church is the S porch, embattled and with a unique canopied and crocketed STOUP inside. - FONT. Perp, octagonal, with traceried and cusped panels. - BENCHES. Some in the nave C15, with little decorative buttresses. - STAINED GLASS. In a S window fragment of a kneeling figure. - PLATE. Chalice, 1569 ; Paten, 1696.

ST MARY MAGDALENE. The stone built church stands like a miniature model on the grass, N of the barns of a big farm. The W tower starts broad and then, by means of hips, goes narrower. The tower windows seem to be of the late C14. The nave and chancel windows are Perp and of modest dimensions. There is inside no structural division between the two parts. The only more ornamental part of the church is the S porch, embattled and with a unique canopied and crocketed STOUP inside. - FONT. Perp, octagonal, with traceried and cusped panels. - BENCHES. Some in the nave C15, with little decorative buttresses. - STAINED GLASS. In a S window fragment of a kneeling figure. - PLATE. Chalice, 1569 ; Paten, 1696.

Caldecote. Here, between the Roman Way and the Icknield Way which meet at Baldock, are wide hedgeless fields of oats and barley, wheat and hay, waving blue-green or gold against the horizon; and planted among them, without street or wall, is the church, the farm, and a group of cottages. There is no road through, and few come this way, but many must have lived here under Roman rule, for several urns and 500 Roman coins have been found hereabouts. Great thatched barns stretched along two sides of the churchyard, dwarfing the little mainly 15th-century church which wears its red-brick restorations so charmingly. By the ancient door is a holy water stoup with a high decorated canopy, one of the finest in Hertfordshire, a strange find in this rough and lonely place. The font, carved with emblems of the Passion, is 500 years old, and the church has other ancient possessions - some 15th-century glass with part of a kneeling figure, an Elizabethan chalice, and a bell hung in Charles I’s days. The Old Rectory of timber and plaster keeps traces of its 16th-century builders.

Friday 9 September 2011

Newnham

St Vincent was being restored, or at least touched up, when I visited - this seems to be happening to me a lot recently, perhaps instead of Spring cleaning churches Autumn clean so it was open (I don't know what its normal status is but the tone of their website sounds welcoming).

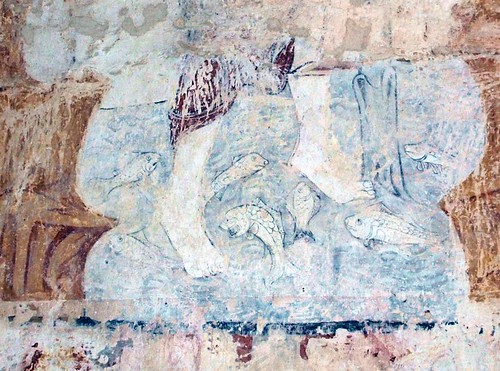

As well as two excellent brasses there are the very faded remains of three wall paintings; one a St Christopher in which you can clearly see the bottom of his robe, legs and fish around his feet and less clearly his hand and staff, another could be a devil in a circle but it's very hard to tell, and by a window what could be the remains of a saint.

The church website says: Substantial fragments can be seen of murals dating from the 14th and 15th centuries (some may be as early as the 13th century). They represent the lower half of St Christopher - his feet, the base of his staff, cliffs and some predatory fish in the stream. Alas the upper half of the saint with the infant Christ on his shoulders was destroyed with the construction of the Victorian roof.

Other intriguing wall paintings await conservation: a mysterious circle with figures of strange beasts, and a human figure close to the pulpit. In fact there are traces of colour underneath the limewash all over the chancel. A number of votive crosses on the outside of the door arch were scratched by pilgrims and other travellers seeking the protection of St Vincent on their journey, and other graffiti can be seen around the doorway to the belfry turret - a fish and a windmill.

In the chancel there are some fine 15th century brasses and some handsomely lettered memorials of the 17th and 18th centuries on the walls and floor. There is a small and attractive early 19th century gothic organ; the 14th century font is also worthy of note. The somewhat dreary appearance of the badly weathered wall cladding - part of the 19th century 'improvements' - belies the tranquil simplicity of the interior. This cladding is in process of gradual removal as and when funds allow. The most recent work can be seen on the east face of the tower.

I totally agree with "the tranquil simplicity" - it's lovely.

ST VINCENT. A small church, but with W tower with stairturret, S aisle and clerestory, and S porch. All this appears Perp, but the chancel has two small C13 lancet windows and the others of the early C14. And inside both the tower arch and the short arcade with low octagonal piers and double-chamfered arches are evidently C14. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, with quatrefoil panels and shields on the bowl and blank arcading on the stem. - PLATE. Chalice and Paten, 1568. - TAPESTRY. 1949, by Percy Sheldrick in the style of 1500, in memory of Reginald Hine, the Hitchin historian. - BRASSES. Man, two wives and children, late C15 (chancel). - Joane Dowman d. 1607 and children (chancel).

Newnham. Its medieval church has facing it a row of cottages fashioned from the 17th-century malting house of the old manor. The church itself has kept its 14th-century porch, with the old roof and carved angels, and the three medieval centuries are still represented by the chancel of the 13th, the arcade and aisle of the 14th, and the clerestory of the 15th. The 14th century gave the church a tower by cutting off a bit of the nave and building two side arches within the original walls to support the weight. The font is 500 years old. There are fragments of medieval glass, an Elizabethan chalice, a bell of Shakespeare’s time with an inscription no one can understand, and two family groups in brass. One group pictures a 15th-century man with his two wives and four children, the other is of a Jacobean lady, Joane Dowman, with six or seven daughters.

As well as two excellent brasses there are the very faded remains of three wall paintings; one a St Christopher in which you can clearly see the bottom of his robe, legs and fish around his feet and less clearly his hand and staff, another could be a devil in a circle but it's very hard to tell, and by a window what could be the remains of a saint.

The church website says: Substantial fragments can be seen of murals dating from the 14th and 15th centuries (some may be as early as the 13th century). They represent the lower half of St Christopher - his feet, the base of his staff, cliffs and some predatory fish in the stream. Alas the upper half of the saint with the infant Christ on his shoulders was destroyed with the construction of the Victorian roof.

Other intriguing wall paintings await conservation: a mysterious circle with figures of strange beasts, and a human figure close to the pulpit. In fact there are traces of colour underneath the limewash all over the chancel. A number of votive crosses on the outside of the door arch were scratched by pilgrims and other travellers seeking the protection of St Vincent on their journey, and other graffiti can be seen around the doorway to the belfry turret - a fish and a windmill.

In the chancel there are some fine 15th century brasses and some handsomely lettered memorials of the 17th and 18th centuries on the walls and floor. There is a small and attractive early 19th century gothic organ; the 14th century font is also worthy of note. The somewhat dreary appearance of the badly weathered wall cladding - part of the 19th century 'improvements' - belies the tranquil simplicity of the interior. This cladding is in process of gradual removal as and when funds allow. The most recent work can be seen on the east face of the tower.

I totally agree with "the tranquil simplicity" - it's lovely.

ST VINCENT. A small church, but with W tower with stairturret, S aisle and clerestory, and S porch. All this appears Perp, but the chancel has two small C13 lancet windows and the others of the early C14. And inside both the tower arch and the short arcade with low octagonal piers and double-chamfered arches are evidently C14. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, with quatrefoil panels and shields on the bowl and blank arcading on the stem. - PLATE. Chalice and Paten, 1568. - TAPESTRY. 1949, by Percy Sheldrick in the style of 1500, in memory of Reginald Hine, the Hitchin historian. - BRASSES. Man, two wives and children, late C15 (chancel). - Joane Dowman d. 1607 and children (chancel).

Bygrave

St Margaret of Antioch is bizarre. Consisting of a barn like nave and a small chancel, it is towerless and instead has a semi octagonal turret with a bellcote on top and is seemingly randomly plonked down in the middle of a farmyard. I wondered whether it was a converted barn but Mee says it's a Norman nave with a 14th century chancel. Sadly it was locked with no keyholder listed so I was unable to explore inside the curious building (a quick Google shows that it's open at the weekends).

ST MARGARET. Nave and chancel only, with a polygonal W turret to give access to the bells. Norman S doorway with one order of colonnettes and one fat roll-moulding in the arch. The nave E angles are strengthened by Roman bricks. The chancel with the chancel arch seems late C14. - FONT. Octagonal with rectangular panels showing the Instruments of the Passion. - PULPIT. With an attached C17 iron hour-glass and bits of re-used C15 panelling. - BENCHES. Some with poppyheads. - SCREEN. C15 with simple Perp tracery. - COMMUNION RAILS. C17 with long sausage-shaped balusters.

ST MARGARET. Nave and chancel only, with a polygonal W turret to give access to the bells. Norman S doorway with one order of colonnettes and one fat roll-moulding in the arch. The nave E angles are strengthened by Roman bricks. The chancel with the chancel arch seems late C14. - FONT. Octagonal with rectangular panels showing the Instruments of the Passion. - PULPIT. With an attached C17 iron hour-glass and bits of re-used C15 panelling. - BENCHES. Some with poppyheads. - SCREEN. C15 with simple Perp tracery. - COMMUNION RAILS. C17 with long sausage-shaped balusters.

Bygrave. A rough lane from the Icknield Way leads to this quiet little place on a saddle of the Chilterns, where is a church, a rectory, a manor farm, and little else. Round the farm are ditches and banks dug to protect a huge double enclosure, 17 acres in all, perhaps the defences of some British tribe before the Romans tramped down Icknield Way. All that is known for certain is that about 550 years ago Sir John Thornbury, who lies at Little Munden, had his manor here, and made the ditches into moats round his house filling them with water for better protection from the bands of marauders wandering the country in those days, the miserable days when men still remembered the Black Death which halved the population of England.

The church was two centuries old when Sir John entered its Norman nave, as we do, through a doorway with scalloped capitals, much patched after 800 years. The font is 500 years old and is the loveliest thing here, with angels round its stem and reminders of the Crucifixion round the bowl, among them the cock that crowed and Judas’s bag of silver. The windows, like the turret leading to the bellcote, are mostly 15th century. The chancel is 14th. The altar table and altar rails were made in the 17th century, and about that time someone put the coat-of-arms on the top of the rood screen, which is 15th. The choir stalls with poppyheads and the screen tracery used on the new pulpit are also 15th century. The pulpit has still the iron stand which held the hourglass 300 years ago. One who preached his last sermon watching it while the sands of 1725 were running out was Peter Feuillerade, a Huguenot who found sanctuary here from French persecution. His name is on a gravestone in the chancel. The graves in the smooth turf outside are like flower beds, with only a metal disc on each to show who lies beneath, no more than the label a gardener puts in to remind him of the seeds he has planted.

Radwell

All Saint's unprepossessing exterior conceals an astonishing array of monuments and brasses - it's like the Tardis! Sadly apart from the monuments it's very sterile with little or nothing else of interest.

ALL SAINTS. Small church, mostly of the C19. No tower; but at the W end of the nave the last bay has an arch as if for a tower. - Carved ROYAL ARMS above C14 chancel arch. - COMMUNION RAILS. Early C17 square tapering balusters. - PLATE. Chalice, 1576 (1566?); Paten, 1793; two C18 plated Chalices and Patens. - MONUMENTS. Brass to William Wheteaker, wife, and son who d. 1487; small figures (chancel). - Brass to John Bele d. 1516 and two wives (nave). - Brass to Elizabeth Parker d. 1602 (chancel). - Two small epitaphs with kneeling figures, 1595 and 1625. - Monument to Mary Plomer d. 1605, the one object in the church describing a visit. Plinth with kneeling children, pilasters l. and r., achievement on top, and nearly life-size frontally seated effigy with baby by her side. Her foot rests on a skull, her hand holds an hour-glass. The carving is thoroughly rustic. The creases in the sleeve are still done with exactly the same carving convention as at Chartres about 1150.

ALL SAINTS. Small church, mostly of the C19. No tower; but at the W end of the nave the last bay has an arch as if for a tower. - Carved ROYAL ARMS above C14 chancel arch. - COMMUNION RAILS. Early C17 square tapering balusters. - PLATE. Chalice, 1576 (1566?); Paten, 1793; two C18 plated Chalices and Patens. - MONUMENTS. Brass to William Wheteaker, wife, and son who d. 1487; small figures (chancel). - Brass to John Bele d. 1516 and two wives (nave). - Brass to Elizabeth Parker d. 1602 (chancel). - Two small epitaphs with kneeling figures, 1595 and 1625. - Monument to Mary Plomer d. 1605, the one object in the church describing a visit. Plinth with kneeling children, pilasters l. and r., achievement on top, and nearly life-size frontally seated effigy with baby by her side. Her foot rests on a skull, her hand holds an hour-glass. The carving is thoroughly rustic. The creases in the sleeve are still done with exactly the same carving convention as at Chartres about 1150.

Radwell. Here the River Ivel becomes a placid lake, with many a brood of waterfowl sheltering in its reeds. The mill has ceased to work, and trout are hatched in the quiet waters. The old folk of Radwell are here for us to see in the small medieval church above the river. The oldest feature is the chancel arch of about 1340, but the walls are probably earlier; it was refashioned in the 15th century. It has a pillared font of the 15th century, a Tudor chalice, two ancient bells, a Jacobean chest, and Jacobean altar rails; but its best possessions are three interesting sculptures and brass portraits of three centuries.

The brass portraits show us William Wheteaker and his wife, their son between them in his priest’s robes, holding a chalice; he was vicar here in 1492. Small brass figures by the pulpit are of John Bele and his two wives in 16th-century dress; one wife has two little sons with her, the other has lost the portraits of two daughters. A fine big brass shows John Parker’s wife in the rich dress and cap of Queen Elizabeth I’s days. There is another Tudor John Parker, "lord of the manor and of all this little town," sculptured with his wife and son kneeling one behind the other. Facing them is a lady sitting in a chair, a stiff little statue of Mary Plomer, "vertue’s jewel, bewtie’s flower." She must have been a neighbour of the Parkers, and her death (in 1605) must have been a village tragedy, for she was only 30 and she was bringing her 11th child into the world. She wears a ruff, and over her head is a mantle; her baby lies in swaddling clothes beside the hourglass in her hand, and at her feet kneel the other ten children. She was a dear lady, we gather from her epitaph:

So that the stone itself doth weep

To think of her which it doth keep.

Weep, then, whoe’er this stone doth see,

Unless more hard than stone thou be.

Kneeling close by is Will Plomer, dressed in his armour, who, left alone with these ten little ones, took another wife to mother them; her monument is with the rest, decorated with three quaint animals.

High Cross

St John was, as expected, locked with no keyholder listed but as it's a 19th century creation I rather suspect the interior would be as bland as the exterior.

ST JOHN THE EVANGELIST, 1846, by Salvin. Grey stone with a SE steeple and a red brick Vicarage behind. Architecturally not specially interesting, but exhibiting an interesting contrast between the STAINED GLASS of the E and W windows. That in the E by Kempe, an early work of 1876, with his typical full forms and rather overdone yellows. That on the W was designed by Selwyn Image and dates from c. 1893. It is most extraordinary for that date, evidently with knowledge of what Burne-Jones had done for Morris & Co. windows, but entirely original in the sombre glowing colours and the rather mannered, Ravennesque central figure of Christ. The diagonal trails of leaves above and below the figures are charming, as are all the decorative features. The window might easily be misdated as modern English work of c. 1930.

ST JOHN THE EVANGELIST, 1846, by Salvin. Grey stone with a SE steeple and a red brick Vicarage behind. Architecturally not specially interesting, but exhibiting an interesting contrast between the STAINED GLASS of the E and W windows. That in the E by Kempe, an early work of 1876, with his typical full forms and rather overdone yellows. That on the W was designed by Selwyn Image and dates from c. 1893. It is most extraordinary for that date, evidently with knowledge of what Burne-Jones had done for Morris & Co. windows, but entirely original in the sombre glowing colours and the rather mannered, Ravennesque central figure of Christ. The diagonal trails of leaves above and below the figures are charming, as are all the decorative features. The window might easily be misdated as modern English work of c. 1930.

High Cross. It is only a hamlet on the Old North Road, but it spans the years from the time when Caesar’s fleet patrolled our shores to the days when HMS Achilles sank a German raider in the Great War. The white ensign flown by the Achilles in the war hangs in the church, and on a memorial below the flag are the names of a boat’s crew who perished in the fight. It is the most striking possession of this 19th-century church.

Making his home here when we called we found the only living man who had won the VC twice, Colonel Arthur Martin-Leake, a surgeon who first won his VC with Baden-Powell in South Africa, and won it again in the Great War for the same devotion to wounded under heavy fire.

At Youngsbury, south of High Cross, is a fine Georgian mansion ringed by trees, with grounds in which the remains of a Roman house were found about 200 years ago. There are two ancient burial mounds near by.

Making his home here when we called we found the only living man who had won the VC twice, Colonel Arthur Martin-Leake, a surgeon who first won his VC with Baden-Powell in South Africa, and won it again in the Great War for the same devotion to wounded under heavy fire.

At Youngsbury, south of High Cross, is a fine Georgian mansion ringed by trees, with grounds in which the remains of a Roman house were found about 200 years ago. There are two ancient burial mounds near by.

Wyddial

Externally St Giles is architecturally easy on the eye but inside it's a real eye opener with lots of good brass (I particularly like Margaret Plumbe's), Tudor brick built north side and some nice Jacobean screens in the north chapel with a very good modern copy in the tower arch but its crowning glory is the Flemish glass in the north aisle depicting some of the Passion sequence.

The glass has been reset surrounded by hideous Victorian glass and is very mixed up. The sequence runs starting at 9 o'clock and going clockwise, I think, as follows:

Looking north the window on the left - 9. The betrayal with Peter cutting off the servant's ear, 12. Christ's trial before the Sanhedrin, 3. Christ before Caiaphas. 6. Christ before Pontius Pilate.

The glass has been reset surrounded by hideous Victorian glass and is very mixed up. The sequence runs starting at 9 o'clock and going clockwise, I think, as follows:

Looking north the window on the left - 9. The betrayal with Peter cutting off the servant's ear, 12. Christ's trial before the Sanhedrin, 3. Christ before Caiaphas. 6. Christ before Pontius Pilate.

The right hand window - 9. Crown of thorns. 12. Pilate washing his hands, 3. Either Christ's arrest in the Garden or his mocking & beating at the house of Caiaphas, 6. Scourging of Christ.

ST GILES. A Perp church, over-restored in the C19. Unbuttressed W tower, C19 S porch. The special and great interest of the church is its N aisle and N chancel chapel, both built of brick and dated by a brass inscription 1532. The windows are of the usual three-light type under one arch, all of brick.* The arcade of three bays has brick piers of the usual type with semi-octagonal shafts and hollows in the diagonals. The arches are treble-chamfered, the middle chamfer being hollow. The arch to the N chapel is also of brick. This triumphant entry of brick into church building is a significant sign of the Tudor age. The N chapel has SCREENS to W and S of elaborate early, C17 design and BOX PEWS to match in the aisle. - STAINED GLASS. In two N windows eight smallish panels with Scenes from the Passion; Flemish mid C16. - PLATE. Paten, 1734. - MONUMENTS. Brass to John Gille d. 1546, with wife and children (chancel). - Brass to Dame Margaret Plumbe d. 1575, large demi-figure praying (chancel wall). - Epitaph to Sir William Goulston d. 1687, with twisted columns carrying a scrolly broken pediment and marble busts in grey niches above the inscription.

* A late C16 N doorway is of stone.

ST GILES. A Perp church, over-restored in the C19. Unbuttressed W tower, C19 S porch. The special and great interest of the church is its N aisle and N chancel chapel, both built of brick and dated by a brass inscription 1532. The windows are of the usual three-light type under one arch, all of brick.* The arcade of three bays has brick piers of the usual type with semi-octagonal shafts and hollows in the diagonals. The arches are treble-chamfered, the middle chamfer being hollow. The arch to the N chapel is also of brick. This triumphant entry of brick into church building is a significant sign of the Tudor age. The N chapel has SCREENS to W and S of elaborate early, C17 design and BOX PEWS to match in the aisle. - STAINED GLASS. In two N windows eight smallish panels with Scenes from the Passion; Flemish mid C16. - PLATE. Paten, 1734. - MONUMENTS. Brass to John Gille d. 1546, with wife and children (chancel). - Brass to Dame Margaret Plumbe d. 1575, large demi-figure praying (chancel wall). - Epitaph to Sir William Goulston d. 1687, with twisted columns carrying a scrolly broken pediment and marble busts in grey niches above the inscription.

* A late C16 N doorway is of stone.

Wyddial. Among its wide fields, threaded by lanes and grassy tracks, with great thatched barns and little thatched cottages of all shapes and ages, we come on a 15th century church scarcely looking its age, but this is confirmed by a broken brass on the chancel wall telling us that the brick aisle was added in 1532 by George Cannon.

The only seats in his aisle are three enormous box-pews over four feet high*. In the windows are eight vigorous little pictures in 16th century Flemish glass showing the approach of Judas, and the Trial, the Scourging, and the Crucifixion. A screen under the tower exactly copies two Jacobean screens, pierced and ornamented with grotesque figures. They enclose the chapel of the Goulstons, whose bygone importance as lords of the manor is marked by numerous memorials, one of 1687 with twisted columns holding up the pompous busts of Sir William and his wife Fredeswyde.

Before the altar are brasses to earlier lords of the manor, one of 1546 showing John Gille with his wife and eight daughters, the sons being missing; but the best portrait brass is a fine head and shoulders of Dame Margaret Plumbe, whose first husband, Sir Robert Southwell, was much occupied in suppressing the monasteries and putting some of their money in his own pocket. It was not his only profitable venture, for he helped to put down Sir Thomas Wyatt’s rebellion and secured some of his lands in the process. Another lady, Margery Disney, who died in 1621, has a curious memorial painted on wood and topped by a skull and crossbones. Over the door hangs the white ensign flown by HMS Inflexible at the Battle of Jutland.

Opposite the church is Wyddial Hall, an 18th-century house built over some 16th-century cellars; and a mile away is the 17th-century house Corney Bury, with three gables and a pillared porch.

* These have been broken up and been re-used to clad the north aisle.

Thursday 8 September 2011

Wormley

The exterior of St Laurence does not forewarn you of the treasures it contains, rendered walls and a wooden bellcote 'tower' screamed restoration. However, although it is over restored enough of the old remains to provide huge interest.

On the south side of the chancel is the Purvey tomb. William Purvey was steward to Sir Robert Cecil, auditor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and joint lord of the manor. His wife Dorothy was granddaughter of Sir Anthony Denny, a favourite of Henry VIII, and one of the counsellors of State for Edward VI. William Purvey died in 1617 at the age of 59, leaving £100 for the erection of this memorial in alabaster. The work is said to have been executed by William Cure the younger, master mason to both James l and Charles I. Also on this side of the chancel is a tablet to Richard Gough, the well known antiquary, whose historical notes are now preserved in the Bodleian Library. On the north side of the sanctuary is a tablet to the memory of Angelette Tooke, daughter of William Woodliffe. The date of her death is May 31st 1598.

On the south side of the chancel is the Purvey tomb. William Purvey was steward to Sir Robert Cecil, auditor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and joint lord of the manor. His wife Dorothy was granddaughter of Sir Anthony Denny, a favourite of Henry VIII, and one of the counsellors of State for Edward VI. William Purvey died in 1617 at the age of 59, leaving £100 for the erection of this memorial in alabaster. The work is said to have been executed by William Cure the younger, master mason to both James l and Charles I. Also on this side of the chancel is a tablet to Richard Gough, the well known antiquary, whose historical notes are now preserved in the Bodleian Library. On the north side of the sanctuary is a tablet to the memory of Angelette Tooke, daughter of William Woodliffe. The date of her death is May 31st 1598.

There are some interesting brasses on the floor of the sanctuary. On the north side can be seen the figures of Edmund Howton and Ann his wife, and five sons. There are probably some daughters missing. There is part of a marginal inscription showing the date 1479. Adjoining this is a gravestone with a brass fragment in Latin, which reads:

"Here lies John Cleve, once Rector of the Church of Wormele who died 22nd. October AD. 1404, whose soul may God accept."

On the south side is a fine brass of Angelette Tooke and Walter Tooke, her husband, their 8 sons and 4 daughters. The stone and brasses originally formed the top of an altar tomb. Angelette Tooke’s memorial tablet is on the north wall. She was the daughter of William Woodliffe and aunt of William Purvey. On the south side may also be seen the brass to John Cok, his wife (with her medieval headdress) and ten sons and daughters. Between the two figures is a strip of brass with trees and a dog pursuing a hare. Above is a small representation of the Trinity. The incomplete marginal inscription is as follows:

"Here lyeth John Cok, Yeoman., and Al... passed God out of this transsitorie ..."

The date is about 1470. Two other brasses of Richard Rufton and Edward Shambroke, both Rectors of this Church, were lost, probably during the rebuilding of the chancel.

ST LAURENCE. To the N of the house and away from the village. A small church consisting of nave and chancel only, to which in the C19 a S aisle, S porch, and stone bellcote were added. One N window of the nave and the N doorway prove the Norman date of the nave. The chancel has been too much restored to preserve any original features. - FONT. Norman, circular, of very uncommon design. An upper frieze of broad upright leaves, and below this panels separated from each other by thick cable mouldings. In the panels rosettes and groups of upright leaves. - PULPIT. Jacobean, with termini-caryatids at the angles. - PAINTING. Last Supper, presented by Sir Abraham Hume of Wormleybury in 1797. Ascribed to Palma Vecchio and purchased from a monastery of Rocchelin Canons near Verona. - PLATE. Flagon, 1625; Pewter Almsdish, 1699. - MONUMENTS. Two white memorial epitaphs, both with sculpture by Westmacott; one to Lord and Lady Farnborough, 1838 and 1837 (with a large kneeling female figure), the other to Sir Abraham Hume d. 1838 (with portrait bust).

ST LAURENCE. To the N of the house and away from the village. A small church consisting of nave and chancel only, to which in the C19 a S aisle, S porch, and stone bellcote were added. One N window of the nave and the N doorway prove the Norman date of the nave. The chancel has been too much restored to preserve any original features. - FONT. Norman, circular, of very uncommon design. An upper frieze of broad upright leaves, and below this panels separated from each other by thick cable mouldings. In the panels rosettes and groups of upright leaves. - PULPIT. Jacobean, with termini-caryatids at the angles. - PAINTING. Last Supper, presented by Sir Abraham Hume of Wormleybury in 1797. Ascribed to Palma Vecchio and purchased from a monastery of Rocchelin Canons near Verona. - PLATE. Flagon, 1625; Pewter Almsdish, 1699. - MONUMENTS. Two white memorial epitaphs, both with sculpture by Westmacott; one to Lord and Lady Farnborough, 1838 and 1837 (with a large kneeling female figure), the other to Sir Abraham Hume d. 1838 (with portrait bust).

Wormley. Its 17th-century manor house on Roman Ermine Street has come down in the world, split into two cottages which share the old chimney stack between them; but at the end of an oak avenue is a church which has grown through the centuries, beginning with a Norman nave and north doorway and ending with a new little bellcot and a south aisle of last century, in which part of a Norman window and a Norman arch have been reset. The old timbers remain in the roofs of the nave and the porch. There is a fine Norman font with ears of corn and cable moulding, a Jacobean oak pulpit with quaint portraits of men and women, and an interesting collection of family groups in brass. One shows an Elizabethan couple with their 12 children, another has 15th century Edward Howton with his wife and three sons, and a remarkable brass shows his contemporary John Cok, with his wife and ten sons, the Trinity appearing above them and dogs chasing a hare below them. Almost reaching the chancel roof is the grand marble-and-alabaster monument of a Jacobean couple, William and Dorothy Purveye, who are sculptured on ledges one above the other, with Dorothy’s child cousin, Honoria Denny, kneeling in a niche below holding a skull. The Pilgrim Trust has in our time restored the monument to its original beauty, and made legible the old inscription which tells us that William Purveye left money for the poor of the parish and “poore schollers in Cambridge” Last of these portrait memorials is the bust of Sir Abraham Hume, who lived at the Bury in the park beside the church and gave the splendid altar painting of the Last Supper by Giacomo Palma, the 16th-century Venetian. Sir Abraham died in 1838, the year after his daughter Lady Farnborough, who is also here kneeling at prayer.

Wormley was the last home of Richard Gough, whose 74 years of happy and fruitful industry closed here in 1809. The son of an East India merchant, he was born in London, and before going to Cambridge at 17 was already a good Latin scholar and the author of an elaborate work on world geography. As an undergraduate he planned his British Topography, and on leaving the university spent 20 years in giving effect to his scheme. Inheriting a fortune, he had means and leisure such as few travelling scholars have enjoyed.

For more than 20 years he tramped England, exploring every county, examining its churches and public buildings, sifting and pondering deeds and charters, and making an immense number of notes on sculptures and inscriptions. His Anecdotes of British Topography followed an exhaustive work on Carausius, the 3rd century Roman who made Roman Britain mistress of the narrow seas, and this was succeeded by a masterly edition of Camden’s Britannia, a labour of love which cost him 16 years of toil.

These books, like his Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain, covering the period between the Conquest and the end of the Tudor Age, were brilliantly written, and finely illustrated and printed. Almost to the end of his days he pursued his travels, enriching his collections, maintaining friendships with scholars and antiquaries throughout the country, and blessed at home by unclouded happiness. At his death he bequeathed his books and manuscripts to Oxford.

Widford

Without being rude St John the Baptist is a run of the mill Hertfordshire church which is set apart by the possession of three interesting wallpaintings (and a rather good chancel ceiling).

The most important is that on the north side of the chancel; dated by Professor Tristram as 1299, it is of "Christ at the Last Judgement", Christ seated on a rainbow, clad in a grey mantle, arms raised to display his wounds, and a two-edged sword issuing from his mouth. For some time the painting was thought to be of St John the Baptist.

The most important is that on the north side of the chancel; dated by Professor Tristram as 1299, it is of "Christ at the Last Judgement", Christ seated on a rainbow, clad in a grey mantle, arms raised to display his wounds, and a two-edged sword issuing from his mouth. For some time the painting was thought to be of St John the Baptist.

On the left side of the East window, the painting shows knots of ribbons on the shoulders of a man, possibly representing a Knight of the Garter, dressed in the mantle of the order. On the opposite side of the East window a bishop holding in his left hand a pastoral staff, the right hand raised in benediction (J. E. Cussons. 1870).

ST JOHN THE BAPTIST. Unbuttressed Perp W tower with low rectangular stair-turret, characteristic tower arch, and recessed spire. Nave and chancel under one roof. S porch C19. In the nave above the S doorway a reset C12 zigzag arch. One S window with Dec tracery, the rest Perp and much of the tracery new. - PILLAR PISCINA. A Norman block capital with the front semicircle decorated; early C12, it seems. - DOOR, C14 with C13 ironwork (says the R. Commission). - WALL PAINTINGS. E; and N walls of chancel. On the N wall Christ of the Apocalypse with sword; c. 1500. - PLATE. Specially good Chalice of 1562 with Paten.

ST JOHN THE BAPTIST. Unbuttressed Perp W tower with low rectangular stair-turret, characteristic tower arch, and recessed spire. Nave and chancel under one roof. S porch C19. In the nave above the S doorway a reset C12 zigzag arch. One S window with Dec tracery, the rest Perp and much of the tracery new. - PILLAR PISCINA. A Norman block capital with the front semicircle decorated; early C12, it seems. - DOOR, C14 with C13 ironwork (says the R. Commission). - WALL PAINTINGS. E; and N walls of chancel. On the N wall Christ of the Apocalypse with sword; c. 1500. - PLATE. Specially good Chalice of 1562 with Paten.

Widford. We may think we hear his laughter echoing, for here he came often to laugh before he came to weep. At the great house of Blakesware his grandmother Mrs Field was housekeeper to the Plumer-Wards, and little Charles played in the park. It was all his, he said - his that gallery of good old family portraits, that marble hall with its mosaic pavements and its twelve Caesars in marble, that lofty Justice Hall with its high-backed chair of authority, terror of a luckless poacher, and his the costly fruit garden and the ampler pleasure garden rising from the house in terraces. Here Mrs Field was housekeeper for over half a century, and Lamb knew the old house and loved it as his home.

Then came the day when, going north, he turned aside to see the great house coming down; a few bricks lay about representing what was once so stately and so spacious. "Death does not shrink up his human victims at this rate," he wrote, and he was indignant then, as we are now, to see the vandal spirit at work in the countryside. Had he seen these navvies at their destroying work, he said, at the plucking of every panel he would have felt the varlets at his heart, and would have cried out to them to spare him something - at least a plank out of the cheerful storeroom in whose window-seat he used to sit and read Cowley. Every plank and panel of the house had magic in it for him. He had the range at will of every apartment, knew every nook and corner, wondered and worshipped everywhere.

Alas, the old house has gone.

Charles Lamb knew everybody here, all the villagers and the old cronies, some of whom come into his poems:

Kindly hearts have I known,

Kindly hearts they are flown.

He tells us in one of his poems of Kitty Wheatley who sleeps in the kirk house, and poor Polly Perkin who had gone to the workhouse; of fine gardener Ben Carter, in ten counties no smarter; and Lily Postilion with cheeks of vermilion; and in some verses which he afterwards suppressed he told of wicked Dorrell who lies in the churchyard here, declaring that had he mended in time he need not

Have groaned in his coffin,

While demons stood scoffing:

You’d ha’ thought him a coughing:

My own father heard him.

It is thought that Old Dorrell cheated the Lamb family of what would have been to them a small fortune, about 2000 pounds.

Many of these people lie in Widford churchyard, and in one corner lies Mary Field herself. She sleeps on the green hilltop hard by the house of prayer, Lamb tells us in his poem on The Grandame, and this is what he says of her:

She served her heavenly Master. I have seen

That reverend form bent down with age and pain,

And rankling malady. Yet not for this

Ceased she to praise her Maker, or withdraw

Her trust in Him, her faith, and humble hope;

So meekly had she learned to bear her cross -

For she had studied patience in the school

Of Christ; much comfort she had thence derived,

And was a follower of the Nazarene.

Truly poignant were his memories of this small place, for here too he had met Anna Simmons, who lived in a cottage, Blenheim, a mile from Blakesware. It was Lamb’s first love, an unrequited one:

Beloved! I were well content to play

With thy free tresses all a summer’s day.